The NZRDA Part-time Employment Study

It comes as no surprise that work-life imbalance is prevalent among resident doctors due to long work hours and the need to meet training requirements.1 Residents have been subjected to increased workloads, time pressure and stress, which has led to a higher rate of burnout compared to the general population.2

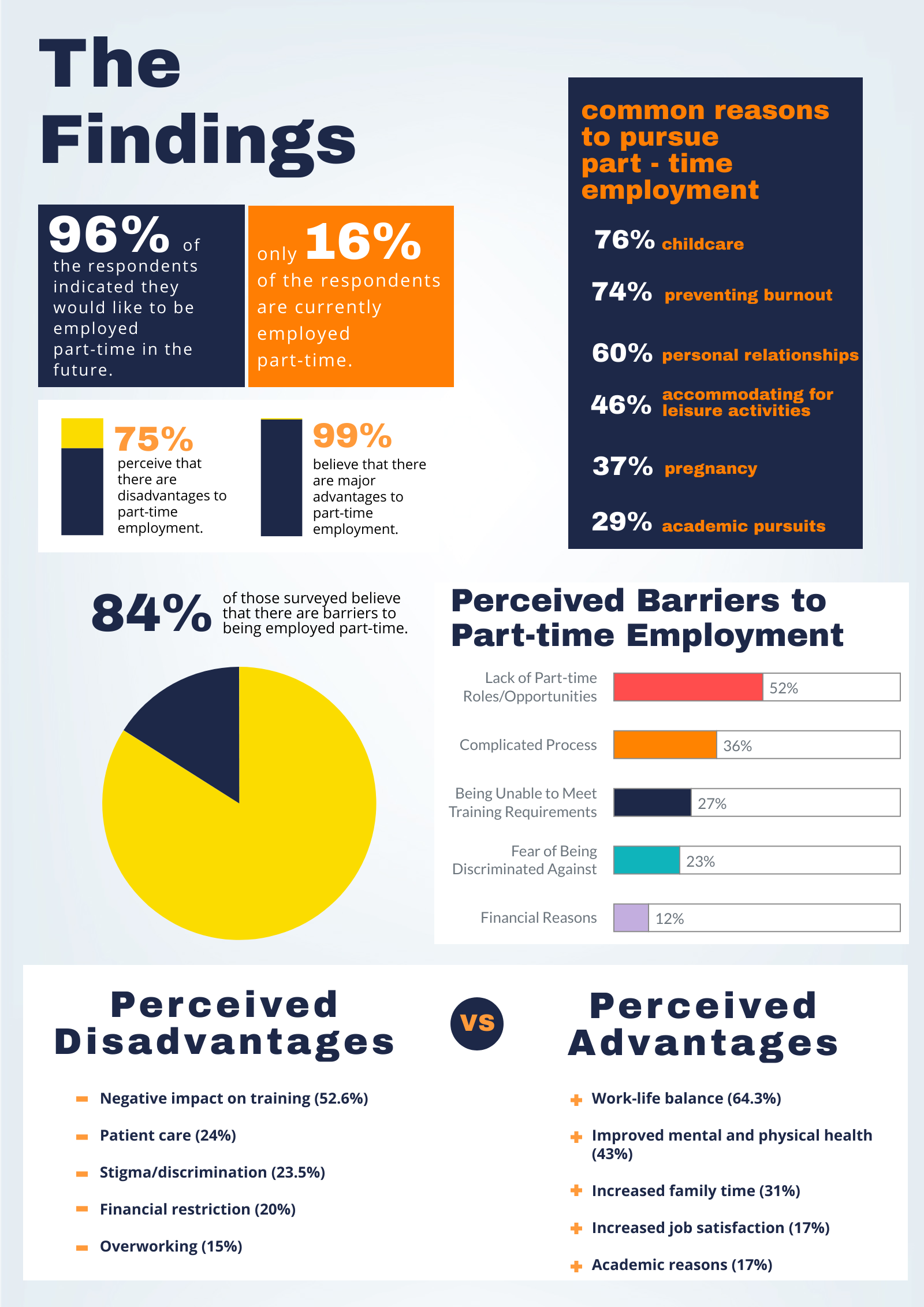

The issue of inadequate access to flexible employment has been raised to National Resident Doctors Engagement (NREG) and the RDA has undertaken an ongoing study on the subject. Interest in part-time employment has increased over the years; however, few are actually able to pursue flexible employment due to structural and non-structural barriers.

The need for part-time employment is present in the healthcare setting, as working long hours is seen as “normal” and is encouraged, even though it is detrimental to the health and wellbeing of residents.3,4 Long work hours leave minimum time and energy for life outside of work.5 Studies show that the fear of being discriminated against has discouraged residents from pursuing part-time employment. This is due to the archaic view that working long hours is essential; and working anything less is seen as weakness or incompetence.6,7 Fear of lack of support from employers, negative attitudes from superiors, and unawareness and misinformation of part-time training and employment are also barriers that continue to discourage residents.3,8 This is consistent with the RDA survey findings.

A study reported that flexible employment has no adverse effect on patient outcomes, satisfaction, education quality and overall patient wellbeing.9 Interestingly, patients have reported higher satisfaction when encountering part-time employees compared to full-timers.10 This may be due to part-time employees having higher humanistic skills.10

An increase in job satisfaction including morale, enthusiasm and productivity has been perceived by managers and part-time employees themselves.11,12,13 Reduced feelings of burnout were reported due to more time available for rest and a personal life.10 Part-time employment that allow for a healthy work-life balance has been found to reduce stress, fatigue and pressure.14

As for employers, the advantages of providing part-time posts include the availability of more candidates for recruitment, increased productivity, lower rates of staff turnover, and employee longevity.15 Job satisfaction of staff influences job retention which may eventually result in a decrease in workforce shortage.10,16

Despite the advantages and need for part-time employment, there is still a lack of positions available to accommodate for flexibility and a life outside of work. In order to increase retention and recruitment, medical organisations need to cater to this demand and provide RMOs with flexible employment options. Increasing flexible employment posts will also facilitate those who are interested in pursuing part-time employment and eventually normalise flexible working arrangements leading to the invalidation of common stereotypes and myths which enforce the infamous unhealthy work-life imbalance within the medical profession.

Case Study: Pilot Emergency Medical Training Programme

A pilot part-time emergency medicine training program commenced in 2017 in the UK. Seventeen trainees took part in this option, working at 80% FTE across 16 hospitals. In the second cohort, an additional 25 trainees joined the program.

An improved work-life balance, job satisfaction and increased likelihood of remaining in emergency medicine was reported. Increased quality of patient care was also observed while the initiative didn’t impact the intensity of workload.

Paediatrics and Obstetrics and Gynaecology will be started their pilot training program in March 2020. The pilot allows resident doctors to work for 50%, 60%, 70% or 80% FTE; however, are unable to select days or hours of work as it may change depending on the needs of the department. The aim of this pilot is to reduce attrition, improve morale and increase recruitment and is under the Enhancing Junior Doctors’ Working Lives initiative.

As a follow up to the survey, we have held focus groups to discuss:

- The need for part-time roles

- Experience of working part-time (including myths and realities)

- Barriers and facilitators of part-time/flexible working arrangements

- Our members’ additional wants and needs

References

1. McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. The Lancet. 2002 Jun 15;359(9323):2089-90.

2. IsHak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. The clinical teacher. 2013 Aug;10(4):242-5.

3. Rich A, Viney R, Needleman S, Griffin A, Woolf K. ‘You can’t be a person and a doctor’: the work–life balance of doctors in training—a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2016 Dec 1;6(12):e013897

4. Lockley SW, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP. Effects of health care provider work hours and sleep deprivation on safety and performance. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007 Nov 1;33(11):7-18.

5. Gander PH, Merry A, Millar MM, Weller J. Hours of work and fatigue-related error: a survey of New Zealand anaesthetists. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2000 Apr;28(2):178-83

6. McMurray JE, Heiligers PJ, Shugerman RP, Douglas JA, Gangnon RE, Voss C, Costa ST, Linzer M. Part-time medical practice: where is it headed?. The American journal of medicine. 2005 Jan 1;118(1):87-92

7. Saalwachter AR, Freischlag JA, Sawyer RG. Part-time training in general surgery: results of a web-based survey. Archives of Surgery. 2006 Oct 1;141(10):977-82.

8. Harries RL, Gokani VJ, Smitham P, Fitzgerald JE. Less than full-time training in surgery: a cross-sectional study evaluating the accessibility and experiences of flexible training in the surgical trainee workforce. BMJ open. 2016 Apr 1;6(4):e010136.

9. Asch DA, Bilimoria KY, Desai SV. Resident duty hours and medical education policy—raising the evidence bar. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017 May 4;376(18):1704-6.

10. Gascoigne, C. (2008). Making part-time work. [PDF]. London: The Medical Women’s Federation.

11. Henry A, Clements S, Kingston A, Abbott J. In search of work/life balance: trainee perspectives on part-time obstetrics and gynaecology specialist training. BMC research notes. 2012 Dec 1;5(1):19.

12. McIntosh CA, Macario A. Part-time clinical anesthesia practice: a review of the economic, quality, and safety issues. Anesthesiology clinics. 2008 Dec 1;26(4):707-27.

13. Whitelaw CM, Nash MC. Job‐sharing in paediatric training in Australia: availability and trainee perceptions. Medical journal of Australia. 2001 Apr;174(8):407-9.

14. Fursman L, Zodgekar N. Making it work: The impacts of flexible working arrangements on New Zealand families. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 2009 Jun 1;35:43-54.

15. Part-time Employment for Physicians. American College of Physicians. https://www.acponline.org/sites/default/files/documents/running_practice/practice_management/human_resources/part_time.pdf

16. Weberg D. Transformational leadership and staff retention: an evidence review with implications for healthcare systems. Nursing administration quarterly. 2010 Jul 1;34(3):246-58.